Understanding C.G. Jung’s Red Book – Part 2

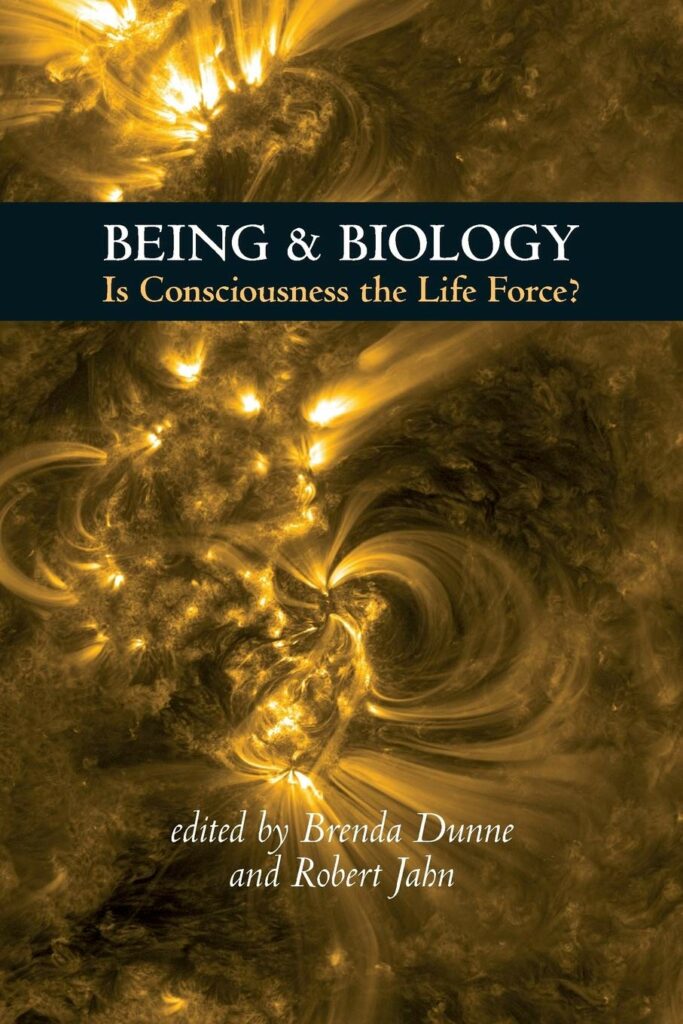

Roger Woolger continues his analysis of Jung’s Red Book, a landmark in the history of psychology and for philosophical thinking in Western Culture. The book is contains calligraphy and symbolic paintings provided by Jung himself. Anyone seriously interested in Jung needs to have a copy of this book. This is the second half of a comprehensive review, and a more extensive version with full references is available in the members section of the website.

Roger Woolger continues his analysis of Jung’s Red Book, a landmark in the history of psychology and for philosophical thinking in Western Culture. The book is contains calligraphy and symbolic paintings provided by Jung himself. Anyone seriously interested in Jung needs to have a copy of this book. This is the second half of a comprehensive review, and a more extensive version with full references is available in the members section of the website.

“The hell fire of life consumes only the best of men; the rest stand by, warming their hands.” – Friedrich Hebbel

Revelation or Psychosis?

The first fully public revelations of the visionary-shamanic side of Jung came shortly after his death with the Swiss publication in 1961 of Träume, Erinnerung, Gedanken. Its translation was soon to take the English speaking world by storm as Memories, Dream, Reflections (1962). The extraordinary chapter ‘Confrontation with Unconscious’ then revealed to the greater world for the first time glimpses of the visions that were the source and inspiration for all of Jung’s subsequent psychological theories and writings. Now, with the publication of the Red Book, we can see that this stunning chapter is only the tip of the iceberg, a tiny part of the greater revelations of Jung’s inner journey, what he called his nekya, his journey to the land of the Dead.

His break with Freud, about which much has been written, had left him desolate. He writes of his state of mind that ‘after the parting of the ways with Freud, a period of inner uncertainty began for me. It would be no exaggeration to call it a state of disorientation. I felt totally suspended in mid-air, for I had not yet found my own footing. It was a period of profound emptiness, a void…’ Nothing had energy for him any more.

He decided on an experiment, a method he later called active imagination: ‘I said to myself, ‘Since I know nothing at all, I shall simply do whatever occurs to me.’ Thus I consciously submitted myself to the impulses of the unconscious.’ (Memories, p.173)

By allowing himself to sit in this emptiness, assisted by playing with childhood building blocks, Jung found images from childhood would emerge spontaneously. Little did he know he had opened the gates of hell. Before long the experiment turns into an uncontrollable nightmare. By October 1913 he was having huge visions of universal devastation, of ‘oceans of blood’ all over Europe.

I saw a terrible flood that covered all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps. It reached from England up to Russia, and from the coast of the North Sea right up to the Alps. I saw yellow waves, swimming rubble, and the death of countless thousands. … I also saw a sea of blood over the northern lands.

These words were actually first written on the very cusp of the ‘Great War.’ For all that has been written about his break with Freud causing his near mental collapse, the Red Book makes clear that in the years 1913-1916 Jung was not brooding on his lost position of prominence in the world of psychoanalysis, but on the seeming breakdown of western civilisation. Well aware that he had all the clinical symptoms of schizophrenia, he nevertheless persisted, as his own shaman, to seek meaning and method in his own madness. Never certain as to what horrors ‘the spirit of the depths’ would next expose him to, it is no wonder that he slept for much of this period with his Swiss army revolver loaded in a drawer next to his bed, in case one more outrageous dream would push him over the edge. Once the Great War broke out he recognised these as psychic premonitions and not signs of his own impending madness. If anyone was going mad, it was the whole of Europe. It was one of the many collective burdens he would have to bear as shaman.

When psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott reviewed Memories, Dreams, Reflections, he said memorably that ‘Jung was insane and healed himself, while we are still trying to recover from Freud’s sanity.’ It is a neat clinical trope but sidesteps the deeper issues that Jung and his Red Book raises about sanity, madness the price of being ‘civilised.’ The Red Book is compelling evidence that in allowing himself to let in this throng of spiritual visitors from the Land of the Dead, that Jung knowingly took upon himself – at great risk to his sanity and with a presumptuousness he clearly recognised as potential spiritual inflation – nothing less than the rejected and repressed pagan and oriental shadows of the whole of western, which is to say, Judeo-Christian civilisation.

Historian Oswald Spengler and notably poets and writers Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot and James Joyce were also doing something similar at this juncture in history – and each would struggle with depression and near-psychosis – but no one seems to have gone so far into the murky depths of the lost soul of our culture than Jung. In this sense he is the Dante of modern times, braving the depths of the inferno of the unconscious mind, going far beyond Freud or practically anyone else. In the Red Book we have the full context of his experiment, which opened him to Europe’s ‘collective’ nightmare and led him to confront the vast forgotten power that stems from the spirit of the depths.

This was and remains a stupendous achievement. For against considerable odds Jung succeeded where many would have caved in to alcohol, depression or turned into some wild-eyed rambling eccentric. Jung’s discovery of his own soul, his quasi-Augustinian confessions that come to form part of the magnificent and deeply moving opening of the Red Book and his descent to hell could just as easily ended as a case study of schizophrenia.

The Night Sea Journey

“I will go down to self annihilation and Eternal Death Lest the Last Judgment come and find me unannihilate. And I be seized and delivered into the hands of mine own Selfhood.” – William Blake

How the Liber Novus starts: Jung’s ‘Answer to Nietzsche’ The Way of What is to Come (Der Weg der Kommende) is the title that appears on the grand and magnificently crafted first illuminated manuscript page of Jung’s great book. The title he engraved is Liber Novus, but is commonly it referred to as The Red Book. It was manifestly his intention that when we open the first part, the Liber Primus of his book – and the stunningly reproduced facsimile of the calligraphic Red Book is similarly impressive – that we are the presence of a mighty work of prophecy and wisdom whose utterances are to be received with reverence and awe. Its bulk and heft make one think of those huge Protestant Bibles that graced so many chapels and homes during the Gutenburg era. Yet a soon as we see Jung’s meticulously illuminated calligraphy we also feel we are at the same time transported to the Middle Ages. The leading voice in the opening page is actually that of the Old Testament prophet Isaiah proclaiming ‘the suffering servant,’ who was ‘despised and rejected of men’ (texts familiar to British readers who know Handel’s Messiah). These proclamations are interwoven with a resonant quote about the birth of Christ as the Logos, taken from Jung’s ‘beloved’ Gospel of John. A new birth is proclaimed, a fervent call to renewal which is as orthodox and yet as personal an expression of Christian faith as the opening Kyrie of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis . But it soon turns out to be a misleading guide to what will follow, and in no way prepares us for many of the pagan visions, mythic beings and magical invocations that we will meet.. And least of all does it prepare us for the quasi-Gnostic treatise The Seven Sermons of the Dead that appears towards the end of the calligraphic volume. The opening of the Red Book is Jung’s oblique proclamation, stemming, as we shall learn, from the authority of his inner teacher, Philemon, of the coming of a renewed epiphany of the Christ, but one where the new birth will not be through any institution or church of some great charismatic leader, but a re-birth within the soul of every human being (this was the deep understanding that came to him from Meister Eckhart). We might call the opening of the Red Book Jung’s consciously wrought ‘Answer to Nietzsche.’ For later, in the Liber Secundus the hosts of the dead tell Jung that they are in need of salvation and that they ‘were led by a prophet whose proximity to God had driven him insane’ (Red Book, p. 297); that prophet is clearly Nietzsche.

The Spirit of this Time and the Spirit of the Depths

But before he can reveal the full nature of his extraordinary visions Jung is impelled to tell the poignant story of how, in late 1913 at the age of 38 and at the apogee of his extraordinary career, and his years in the Psychoanalytic movement with Freud, he had been seduced by ‘the spirit of the time,’ and had essentially lost his soul. After the painful reversal of his career, his fall from fame and prominence, he sees that the necessity of his ‘descent to hell’ was the prompting of a radically different force, namely ‘the spirit of the depths’ that he had so grievously neglected. ‘I had to become aware,’ as he writes ‘that I had lost my soul, or rather that I had lost myself from my soul, for many years’. Here are some of the moving opening words of his ‘confession’:

Filled with human pride and blinded by the presumptuous spirit of the times, I long sought to hold that other spirit away from me. But I did not consider that the spirit of the depths from time immemorial and for all the future possesses a greater power than the spirit of this time, who changes with the generations. The spirit of the depths has subjugated all pride and arrogance to the power of judgment. He took away my belief in science, he robbed me of the joy of explaining and ordering things, and he let devotion to the ideals of this time die out in me. He forced me down to the last and simplest things.

He had espoused a false attitude to science which now he had to abandon, submitting to a sacrificium intellectualis that will require him to sit long in the darkness of ‘unknowing’ that a medieval mystic quoted earlier describes as the necessary path of spiritual purification.

‘Without the soul there is no way out of this time’

Mixed in with the visions of chaos all over Europe are some of the loveliest passages in the Red Book. He tells how he finally rediscovers the soul he has lost in his years of worldliness and fame. When I had the vision of the flood in October of the year 1913, it happened at a time that was significant for me as a man. At that time, in the fortieth year of my life, I had achieved everything that I had wished for myself. I had achieved honour, power, wealth, knowledge, and every human happiness. Then my desire for the increase of these trappings ceased, the desire ebbed from me and horror came over me. The vision of the flood seized me and I felt the spirit of depths, but I did not understand him….

My soul, where are you? Do you hear me? I speak, I call you – are you there? I have returned, I am here again. I have shaken the dust of all the lands from on my feet, and I have come to you, I am with you. After long years of long wandering, I have come to you again….

As he listens to his long lost soul, he is filled with remorse for having so wantonly immersed himself in the spirit of the time: I still laboured misguidedly under the spirit of this time, and thought differently about the human soul. I thought and spoke much of the soul. I knew many learned words for her. I had judged her and turned her into a scientific object. I did not consider that my soul cannot be the object of my judgment and knowledge; much more are my judgment and knowledge the objects of my soul. Therefore the spirit of the depths forced me to speak to my soul, to call upon her as a living and self-existing being.

A passage cited from the Black Books by Aniela Jaffé sums up this moving dialogue:

The spirit of the depths sees the soul as an independent, living being, and therewith contradicts the spirit of the times for whom the soul is something dependent on the person, which lets itself be ordered and judged, that is a thing whose range we can grasp. Before the spirit of the depths this thought is presumption and arrogance. Therefore the joy of my re-discovery was a humble one…without the soul there is no way out of this time.

From the Life and Work of C.G. Jung (1989), p. 172

Jung’s Descent to Hell

…easy is the descent to Avernus: night and day the door of gloomy Dis stands open; but to recall thy steps and pass out to the upper air, this is the task, this the toil! Virgil, Aeneid, VI, (quoted in Jung’s Psychology and Alchemy p. 39)

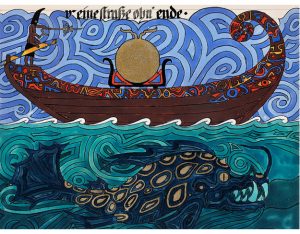

When Jung’s visions of the bloodbath that was sweeping over Europe finally subside, Jung’s soul leads him into the desert, the equivalent of Eliot’s Waste Land. This is the beginning of his journey to the land of the Dead, which he called his nekya, the Greek word for the ‘Night Sea Journey’ made by Odysseus to the place where the shades dwell in Hades, as told in Book 11 of the Odyssey. This descent, traditionally referring either to an initiation or some kind or a propitiation of the Dead, recurs in Egyptian sacred texts, Virgil’s Aeneid, certain Gnostic texts, Dante, and the Walpurgisnacht in Goethe’s Faust. Jung is painfully aware he is following a well- trodden path. He was also fond of the Virgil quote at the head of this section which comments on the descent of Aeneas.

After several nights and various strange encounters he has visions, previously reported in Memories, of a dark cave with a corpse, a red stone, a black scarab, a red sun, thousands of serpents and a huge stream of blood:

I stand in black dirt up to my ankles in a dark cave…. whose bottom is covered with black water… I catch a glimpse of a luminous red stone…the frightful noise of shrieking voices … something wants to be uttered. …I hear the flow of underground waters. I see the bloody head of a man on the dark stream. Someone wounded, someone slain floats there. I see a large black scarab floating past on the dark stream….

In the deepest reach of the stream shines a red sun, radiating through the dark water…terror seizes me…small serpents on the dark rock walls, striving toward the depths, where the sun shines. A thousand serpents crowd around, veiling the sun. Deep night falls. A red stream of blood, thick red blood springs up, surging for a long time, then ebbing.

This flood of moribund images now makes much more sense in the context of Jung’s reflections on of his betrayal of his soul that opens Liber Novus. The dead body, the scarab and red sun reveal to him the death of his old ego self, whilst the potential for re-birth emerges from deep down in the earth attended with numerous serpents, bearers of the chthonic energy of the depths (Jung is to have many encounters and transformations at the hands of serpents in his continuing journey). In the language of Indian tantra this could be seen as the awakening of huge kundalini energy in the yogi or shaman (cf. John White (ed.) (1979) Kundalini, Evolution and Enlightenment.)

A further vision of the death of the hero recurs later as the killing of Siegfried. Jung agonises: ‘I felt certain that I must kill myself if I could not solve the riddle of the murder of the hero.’ With time and reflection Jung slowly realises how his personal transformation, demanding a painful sacrifice of his old self, is deeply bound up with the collective fate and unprecedented blood sacrifice of the German people. Because they are his immediate ancestors he feels implicated in this war of horrible ferocity that is about to be waged. This leads directly to meditations on Christ’s sacrifice on the cross and to the shocking realisation that the redemptive power of Christ entailed a journey to the underworld to become identical with his own dark brother, the dragon or serpent. It will be the same serpent that in his encounter with Salomé Jung will wrestle with on the cross till he bled copiously. The psychic agony of holding together upper and lower worlds, dark and light, heaven and hell in a posture of the Cross, will recur later in the Red Book.4 This psychic crucifixion will become the essence of Jung’s later cosmological synthesis, his personal gnostic mystery of the union of opposites which is the key to the Seven Sermons of the Dead.5

After death on the cross Christ went into the underworld and became Hell. So he took on the form of the Antichrist, the dragon. The image of the Antichrist, which has come down to us from the ancients, announces the new God, whose coming the ancients had foreseen…

The rain is the great stream of tears that will come over the peoples, the tearful flood of released tension after the constriction of death had encumbered the peoples with horrific force. It is the mourning of the dead in me, which precedes burial and rebirth. The rain is the fructifying of the Earth, it begets the new wheat, the young, germinating God.

In Jung’s mythological thinking the young green god of re- birth is not only Christ but is another form of the young Dionysus and the dying Osiris. He is also anticipating a life changing dream of ‘the Green Christ’ that will lead him many years later to the study of the alchemists who understood the identity of Christ with the Philosopher’s Stone, the sought after Lapis.

Roger J. Woolger is a Diplomate of the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich and holds degrees in psychology, philosophy and religion from Oxford and London Universities. His doctoral thesis was on The Mysticism of Simone Weil. He has taught Jung at Vassar College, New York and Concordia University, Montreal as Distinguished Visiting Professor. He is also known for his work on past life regression. See further: www.deepmemoryprocess.com

Notes

1. Owen, Lance (2010) “The Hermeneutics of Vision” in The Gnostic 3. Dublin; Lachman, Gary (2010) Jung the Mystic, New York; Robert Moss “Thus Spake Jung” athttp://mossdreams.blogspot.com/2010/05/thus- spake-jung-i.html

2. Neihardt, John G. (ed.) (1932) Black Elk Speaks.

3. Eliade, Mircea (1951) Shamanism, Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Chicago.

4. On the esoteric meaning of the cross linked to the Cosmic Man, anthropos, see Guénon, René (1931/1958) The Symbolism of the Cross. London, Jung, C.G. (1951) Aion, and Woolger (2008) Mystical Body, Man of Light; the Lost Secret of the Cosmic Christ. CD of illustrated lectures from Woolger Institute, Oxford. [email protected]

5. Cf. Jeromson, Barry “Systema Munditotius and Seven Sermons” (2008) Jung History 1, 2https://www. philemonfoundation.org/resources/jung_history/volume_1_issue_2/systema_munditotiusand_seven_sermons_ symbolic_collaborators_in_j