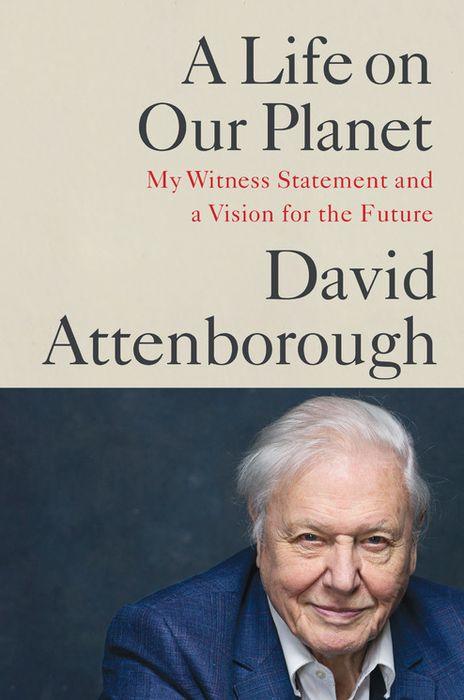

A Witness Statement

Book Review

by David Lorimer

Sir David Attenborough’s witness statement and vision for the future is wise advice that those in charge of our governance systems would do well to heed, but are unlikely to do so as they are in thrall to a dominating oligarchy wedded to the short-term, to power and to solutions that dispense with the human in favour of technology. Some readers may also have seen the Netflix film of the same title, and if you have not yet seen it, I would urge you to do so along with consulting this book for more detail. Sir David is in a unique position in having made documentary films about the planet since the 1950s, during which period he has witnessed the visible declines documented here. The documentary begins in Pripyat in Ukraine, a place of utter desolation since the Chernobyl explosion of 1986 and a parable of what might lie in store if we complacently persist in our current trajectory. This situation came about as a result of bad planning and human error, the very factors at play in ‘the spiralling decline of our planet’s biodiversity.’ 50 years ago we did not have the realisations that we have now and which should impel us to think and act differently.

When Attenborough was born, world population was 2.3 billion, carbon in the atmosphere 280 ppm and remaining wilderness 66%. As of 2020, human population is 7.8 billion, carbon 415 ppm and remaining wilderness 35%. He charts a number of significant developments over his lifetime and the growing realisation that ecosystems and species require protection, that the planet is also a complex ecosystem (Gaia hypothesis), that biodiversity is crucial to life, and that without a global course correction, we will literally consume our life support systems and that beyond certain tipping points civilisation will collapse. All this and the wonders of the natural world are vividly depicted in Attenborough’s many series about life on Earth, summed up in his final film. The ‘efficiency’ of our industrial approach with its large and expensive machinery and boats has become over-exploitative and unsustainable. We have come to regard the Earth as our planet, ‘run by humankind for humankind.’ This current era of ‘Great Acceleration’ is billed as progress, but we are now coming up against a variety of planetary boundaries and are in danger of entering a Great Decline.

Attenborough’s vision is based on the correlation between the planet’s stability and its biodiversity, hence his prescription that we must rewild the world and restore its biodiversity, to which he devotes the third part of the book. He supports Kate Raworth’s doughnut model of economics, relating social foundations with ecological ceilings as an approach that could improve human lives while reducing our ecological impact. This involves moving away from perpetual economic growth, but even green growth, as he points out, is still growth and does not reflect the circular economy of nature. He supports a switch to green energy (though this also uses up precious raw materials), the creation of further marine protected areas and a reduction in meat consumption in order to return industrial farmland to nature and focus on regenerative farming so as to produce more food from less land. He notes that 80% of farmland worldwide is used directly or indirectly for meat and dairy production, which equates to 4 billion of 5 billion farmland hectares, and that a mainly plant-based diet is in any event healthier – he himself has not eaten meat for many years. Reforestation is also critical, but we currently have no way of estimating the value of wilderness and environmental services, hence it is more ‘profitable’ to cut the trees and replace them with oil palm monocultures. This ‘wealth’ represents the commodification of the natural world.

In a chapter on population and planning for ‘peak human’, Attenborough notes that the carrying capacity of the environment for a particular species ‘represents the very essence of balance in nature’ but, unlike other species, humans as a whole have never met our natural ceiling. However, all the signs are that we are currently approaching Earth’s carrying capacity for humanity, and indeed Earth Overshoot Day in terms of regeneration of resources now occurs before the end of July. He discusses the four-stage demographic transition currently underway and the importance of empowering women, although he could also mentioned contraception in this respect. Towards the end of the book, Attenborough discusses how we might achieve more balanced lives in a circular economy, citing some examples of visionary city projects, although we will also require a restructuring of fiscal, legal and accounting incentives, including international laws against ecocide. All this has to involve a radically different attitude to nature, a return to a relational indigenous understanding and practice, which is not just about saving the planet, but rather saving ourselves, and moving beyond intelligence to wisdom. We as people need to demand this from our leaders, which at a minimum means voting for and electing such people then generating the necessary political momentum.