Understanding C.G Jung’s Red Book – Part 3

This is the second part of Roger’s comprehensive review of Jung’s Red Book. Very sadly, Roger passed away shortly after writing this concluding part to his analysis of Jung’s work. His excellent series on the Red Book has proven to be among the most popular articles we have shared, a great testament to Roger’s remarkable insights on this topic.

Mysterium: the Meeting with Elijah and Salomé

This extended episode is part of a visionary meeting in the desert with the Biblical prophet Elijah and his consort, blind Salomé, the slayer of the holy man John the Baptist. Jung came to remember this meeting as one of the most vivid and powerful of all the visions he recorded in the Liber Novus.

An old man stood before me. He looked like one of the old prophets. A black serpent lay at his feet. Some distance away I saw a house with columns. A beautiful maiden steps out of the door. She walks uncertainly and I see that she is blind. ..

“I am Elijah and this is my daughter Salomé.”

A little later after having met two serpents, one black and one white, Elijah takes Jung to a very high summit and shows him there a mighty boulder, like an altar. The prophet stands on this stone and says: “This is the temple of the sun. This place is a vessel that collects the light of the sun.’ Elijah invites Jung to ‘step over to the crystal and prepare yourself in its light,’ then:

A wreath of fire shines around the stone… The foot of a giant that crushes an entire city? I see the cross, the removal of the cross, the mourning. …I see the divine child, with the white serpent in his right hand, and the black serpent in his left hand. I see the green mountain, the cross of Christ on it, and a stream of blood flowing from the summit of the mountain—I can look no longer, it is unbearable—I see the cross and Christ on it in his last hour and torment—at the foot of the cross the black serpent coils itself—it has wound itself around my feet—I am held fast and I spread my arms wide. Salome draws near. The serpent has wound itself around my whole body, and my countenance is that of a lion.

Salomé says, “Mary was the mother of Christ, do you understand?”

I (Jung): “I see that a terrible and incomprehensible power forces me to imitate the Lord in his final torment. But how can I presume to call Mary my mother?”

S: “You are Christ.”

I stand with outstretched arms like someone crucified, my body taut and horribly entwined by the serpent: “You, Salomé, say that I am Christ?”

It is as if I stood alone on a high mountain with stiff outstretched arms. The serpent squeezes my body in its terrible coils and the blood streams from my body; spilling down the mountainside. Salomé bends down to my feet and wraps her black hair round them. She lies thus for a long time. Then she cries, “I see light!” Truly; she sees, her eyes are open. The serpent falls from my body and lies languidly on the ground. I stride over it and kneel at the feet of the prophet, whose form shines like a flame.

E (Elijah): “Your work is fulfilled here. Other things will come. Seek untiringly; and above all write exactly what you see.’

The black serpent coils himself around Jung’s cruciform body, squeezing out his blood. It has the function of coercing him to connect to and to make sacrifice to the power of earth mother principle, so neglected in most forms of Christianity: ‘The serpent is the earthly essence of man of which he is not conscious. Its character changes according to peoples and lands, since it is the mystery that flows to him from the nourishing earth-mother.’

The lion headed god who comes into Jung’s body briefly is an epiphany of Aeon, the solar God of the Orphic and Mithraic Mysteries who rules the cycles of cosmic time and cosmic renewal.(4) This extraordinary many faceted god is also called Phanes. Later he appears in his youthful form in the Liber Secundus of the Red Book where he is central to the regeneration of Izdubar. In the third book, Scrutinies where we meet Jung’s most refined and definitive cosmology, the Seven Sermons, we find Phanes balancing his polar opposite or dark brother Abraxus.

After briefly incorporating Aeon/Phanes, Jung makes an unnerving discovery. In the middle of his agony as he is being crucified, he realizes that Salomé, who has earlier proclaimed herself his sister, now announces that Mary is their mother and that therefore he must be, yes, Christ! Jung comes to understand how strongly every traditional Christian is tied to Mary the Mother of God by a deep Eros bond that keeps him or her in unconscious infantile dependence. To break this dependence and reintegrate the lost earth mother—here in her serpent form—he has now to die on the psychic cross he must bear within him—crucifixion to the four functions and to the four sacred corners.

The conflation of several traditional mysteries in this quite brief extract shows how deeply Jung had become psychically identified with the suppressed religious unconscious of the west and the Biblical and pagan antecedents of Christianity, especially its gnostic counter-currents. The sun temple on the mountain recalls many pagan cults of the sun, of sacred stones, of the omphalos at Delphi and kindred holy mountain sacrifices. The divine child, who presages renewal and a new future, must hold both the dark and light serpents that Jung will struggle with for many nights in the desert. They are the hellish and heavenly energies he must hold together in the crucifixion within his soul, as he labours psychically to give birth to the new religious configuration that must supersede the dead Christianity of this time.

The Christian Desert and the rediscovery of the lost Dionysian

The second book, Liber Secundus, is entitled ‘Images of the Erring’ and takes Jung through a visionary desert which shows him aspects of Hell and which could be said to mirror various aspects of his Christian ancestry and aspects of the Christian and Faust myth whose contradictions and decadence he had never dared consider as fundamentally ‘erring’. (His seemingly blasphemous early dream of God defecating on the cathedral now makes sense as an early prefiguration of these revelations). He encounters a Red Devil and converses with him much as Faust did. In the forest he meets a scholar who is hiding his beautiful daughter in a castle where she guards his library. Jung imagines seducing her as if he were in a romantic novel. But the novel starts to come to life and in a wonderfully comic moment he cries out desperately ‘I am truly in Hell—the worst awakening after death, to be resurrected in a lending library.’

He witnesses the apparent murder of a lowly peasant. He meets an anchorite, perhaps one of his own past lives as a Desert Father but this figure is a dried up thinker who only seems to mirror back to Jung some of his own empty intellectualism. The Devil shows him more of the vastness of Death and he must meditate on yet more visions of horrendous mass slaughter, another sea of blood and unending sacrifice. Finally, he abandons ‘the sad remains of earlier temples and rose gardens’ and the solemnities and barrenness of the Christian desert and is drawn into the sensuality and joy of a Dionysian spring orgy, a Bacchanale! Like the extended pagan scenes of Faust II, the milieu is full of abundant greenery, music, wine and dance.

Luscious-lewd whores giggled and rustled along the walls, wine fumes and kitchen steam and the foolish cackling of the human crowd drew near in a cloud. Hot sticky tender hands reached out for me, and I was swaddled in the covers of a sickbed. I was born into life from below, … I was no longer the man I had been, for a strange being grew through me. This was a laughing being of the forest, a leaf green daimon, a forest goblin and prankster, who lived alone in the forest and was itself a greening tree being, who loved nothing but greening and growing….

He has found his Dionysian Green Man self, the lost shadow of the arid, excessively apollonian and overly ‘spiritual’ part of his Christian soul.

The Healing of Izdubel, the Cosmic Egg

This Dionysian-Bacchic interlude leads us thematically to the great encounter with the giant Izdubel, known nowadays as Gilgamesh. Jung envisions him as a wounded bull god who carries the energy of cosmic renewal and who is identical to Dionysus, Siva, and the Vedic Prajapati, Lord of the Animals.

This Dionysian-Bacchic interlude leads us thematically to the great encounter with the giant Izdubel, known nowadays as Gilgamesh. Jung envisions him as a wounded bull god who carries the energy of cosmic renewal and who is identical to Dionysus, Siva, and the Vedic Prajapati, Lord of the Animals.

Jung seeks the primordial earth power, a power, which belongs to the primordial mother who dwells in the east. Izdubar, by supreme contrast wants to be reborn in the west through the doorway of the setting sun. Both are wounded and both lack something the other has; Jung wants Izdubar’s magical cthonic force; Izdubar craves the light of the western logos, but both are wounded in their respective ways: ‘Knowledge lamed me, while he (Izdubar) was blinded by the fullness of the light’ writes Jung.

Jung actually has great pity for the wounded giant and wants to see him healed. He is fearful, however, that many ‘who have wanted to heal their sick god … were then devoured by serpents and dragons on the way to the land of the sun.’

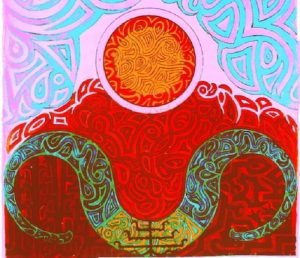

A series of magnificent drawings leading to the opening of the cosmic egg and the birth of the new god, a regenerated Izdubar illustrates the regeneration of Izdubar For three nights Jung assembles a glorious array of incantations and invocations, some his own poetic creations, some drawn from Vedic texts he had been immersed in for many years. It is for me the richest and most moving part of the whole Red Book, full of compassion and parturient care in the birthing of his new god. It is Jung the old shaman-priest, practicing a rite of ancient theurgy.:

I have slain a precious human sacrifice for you, a youth and old man. I have cut my skin with a knife. I have sprinkled your altar with my own blood. I have banished my father and mother so that you can live with me. I have turned my night into day and went about at midday like a sleepwalker. I have overthrown all the Gods, broken the laws, eaten the impure. I have thrown down my sword and dressed in women’s clothing. I shattered my firm castle and played like a child in the sand.

The Coming of Phanes

This powerful series of pictures accompanied by Jung’s rich poetic incantations for the healing of Izdubar mark a pivotal phase of Jung’s visionary journey. The Cosmic Egg which heals Izdubel becomes the agent of a visionary re-birth and marks the splendid arrival of a new figure, who is in every sense an epiphany. This is the luminous figure of Phanes, who is to be central to Jung’s cosmology from this point on. Phanes is the divine child, or puer aeternus, whose spiritual light balances and complements the chthonic energies of Abraxus, who rules creation.

Near the end of his pictorial sequence of incantations Jung has painted a glorious image with calligraphic text of a fiery sun rising out of molten magma supported by two incandescent serpent energies. He titles it hiranyagarbha which is the Vedic Sanskrit name for the Golden Child, Brahma, who is born from the Cosmic Egg. As in the Orphic myth the primordial Eros is born from such an egg and is given the epithet ‘phanes’, which means ‘the Shining or Resplendent One.’ It also becomes another name for the god himself in the Orphic mysteries.

With the birth of Phanes Jung is seized by an outpouring of mystical fervour which results in a series of ecstatic hymns to Phanes, whom he recognises as the luminous principle of immortality and the eternal life the soul. Here is an extract:

Phanes is the God who rises agleam from the waters.

Phanes is the smile of dawn.

Phanes is the resplendent day.

He is the immortal present.

He is the gushing streams.

He is the soughing wind.

He is hunger and satiation.

He is love and lust.

He is mourning and consolation.

He is promise and fulfilment.

He is the light that illuminates every darkness.

He is the eternal day…. (Black Book 7, p. 16).

These hymns are one of the joys of the Red Book and must be appreciated alongside the paintings. Like reading Blake or a medieval Book of Hours they invite reverent meditation. For here, with the epiphany of Phanes one feels Jung’s faith has been reborn.

Roger J. Woolger was a Diplomate of the C.G Jung Institute in Zurich and held degrees in psychology, philosophy and religion from Oxford and London Universities. His doctoral thesis was on The Mysticism of Simone Weil. He taught Jung at Vassar College, New York and Concordia University, Montreal as Distinguished Visiting Professor. He was also known for his work on past life regression.